Evolutionary Ecology / Plant-Animal Interactions

My research focuses on the role of behavior, by both plants and insects, in mediating interactions among the two groups of organisms. The sensory and behavioral attributes of insects, including vision, taste, smell, and touch, as well as a capacity to learn and remember, ultimately shape the insects' ability to interact with and exert selection on plants and on other insects. Similarly, the active behavior of plants allows them to take advantage of insects' sensory and behavioral capabilities.

Current research

Direct and Indirect Effects of a Periodical Cicada Emergence on Trophic Dynamics

The emergence of billions of Brood X periodical cicadas (Magicicada spp.) in the eastern U.S. in the spring of 2021 provided a rare opportunity to quantify the ecological impacts of a massive pulse of insect biomass on the trophic dynamics of eastern deciduous forests. Because Magicicada spp. provide an abundant, nutritious, and accessible food source to the local avifauna, they generate both functional responses (e.g., prey-switching) and numerical responses (e.g., increased reproductive success), which have been documented by our team and others. However, the ecological consequences of these two types of avian responses for the birds’ forest communities remain poorly understood. By altering the strength of the avian trophic cascade in these forests, the Brood X cicada emergence can provide novel insights into how insectivorous birds regulate both herbivore and parasitoid communities and how these impacts, in-turn, influence plant damage and growth.

DEFECATION BIOLOGY (FAECOLOGY!)

My interest in defecation behaviors of animals (and insects in particular) grew out of my studies of frass-flinging by skipper caterpillars. Whereas foraging has been a major focus of ecological and entomological research, its obligate partner, defecation, has been comparatively neglected. Insects exhibit a range of intriguing behavioral and morphological adaptations related to waste disposal in a range of contexts, including predator-prey interactions, hygiene, habitat location, reproduction, feeding, and shelter construction. Some insects, for example, make use of their own excrement as a physical or chemical defense against natural enemies, while others actively distance themselves from their waste material. Internally feeding insects, fluid-feeders, and social insects face particular challenges because their feeding behavior and/or site fidelity makes them especially vulnerable to problems associated with waste accumulation. As is true for foraging, ecological interactions involving defecation may have far-reaching evolutionary consequences and merit further study.

LEARNING IN LEPIDOPTERA

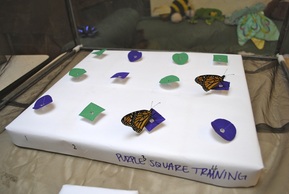

Though most research on insect learning has focused on bees, we have established that Lepidoptera are also very capable learners, both as larvae and adults. Indeed, a capacity for rapid and flexible associative learning allows butterflies to adjust their foraging efforts in response to variable floral resources and to locate appropriate host plants for oviposition. We use both field observations and controlled experiments to address questions concerning innate and learned color, shape and pattern preferences, duration of memory, and reversibility of learned cures.

We have also determined that caterpillars can learn to associate tastes and smells with aversive or appetitive stimuli, and that in some contexts, memories formed in the larvae can survive metamorphosis and subsequently affect adult behavior.

We have also determined that caterpillars can learn to associate tastes and smells with aversive or appetitive stimuli, and that in some contexts, memories formed in the larvae can survive metamorphosis and subsequently affect adult behavior.

Previous investigations

TRI-TROPHIC INTERACTIONS AND THE TEMPORAL STABILITY OF HOST-USE BY AN OLIGOPHAGOUS HERBIVORE

Explaining extant patterns of host plant associations in insect herbivores is a primary goal of insect ecologists. Both plant nutritional quality and the susceptibility of the herbivore to enemies while on the plant can influence host plant suitability. However, the relative importance of these factors, as well as the temporal stability of their interaction, is poorly understood. My colleagues John Lill (George Washington University), Eric Lind (University of Minnesota) and I are examining the ecological factors underlying the recent host expansion of a widespread butterfly, the silver-spotted skipper (Epargyreus clarus), to include several novel non-native plant species. Our investigation, which involves multi-year experimental field manipulations of caterpillars and predators, surveys of plant nutritional quality and predator abundances, and modeling of the parameterized results, will be the first comprehensive investigation of temporal variation in both plant-based (bottom-up) and enemy-based (top-down) measures of fitness for a non-specialist herbivore.

SPIDER-WASP INTERACTIONS, ANT MIMICRY, AND 'DOUBLE DECEPTION'

Divya Uma (PhD 2010) introduced our lab to the study of mud-dauber wasps, with a particular focus on the sensory ecology of interactions between the wasps and their spider prey. Most recently, our investigations of jumping spiders that mimic ants morphologically and behaviorally (including an 'antennal illusion,' in which the spiders hold their first pair of legs above their heads like antennae!) has revealed that the mimics are protected not only from visually-oriented spider predators, but also from chemically-oriented sphecid wasps, as well as their own model ants. To our knowledge, such 'double deception,' in which a single organism sends misleading visual signals to one set of predators while chemically misleading another set, has not been reported.

MALE-MALE COMPETITION IN A PARASITOID WASP

Jean Tsai (PhD 2014) introduced our lab to the study of sexual selection in Nasonia vitripennis (Chalcidoidea: Pteromalidae), a tiny wasp that parasitizes the pupae of flies found in bird nests and carrion. Generally, adult males emerge from hosts before females and fight for access to puparia from which females will eventually emerge. When adult females emerge, they often mate before dispersing from their natal host patch and finding new hosts in which to oviposit. Our research focuses on male-male agonistic interactions and male-female interactions. Specifically, we examined factors influencing male-male contests, the dynamics of these contests, and the role of these contests in determining male mating success.